John Tozzi

March 15, 2016

The lead in the water in Flint, Mich., is a devastating reminder of how closely human health is intertwined with the environment. While the Flint crisis may be an egregious example of cruelty and neglect, the damaging consequences of a broken environment are all around us, a new tally by the World Health Organization shows.

Nearly a quarter of all deaths worldwide are caused by environmental risks like polluted air, dirty water, hazardous workplaces, and dangerous roads, according to the WHO report. The global health authority estimates that 12.6 million deaths in 2012, or about 23 percent of the total, were attributable to such factors.

The burden is greatest on the poorest people in the world, and on the youngest. Mortality from environmental risks is highest in sub-Saharan Africa and low- and middle-income countries in Asia.

Source: WHO

These risks disproportionately affect children “because of their innate vulnerability,” said Frederica Perera, director of the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health and professor at the university’s Mailman School of Public Health. And they aren’t theoretical. “These impacts are being felt today, worldwide, most severely in developing countries but also in this country,” Perera said. “We’ve reported impacts of pollution right here in New York City.”

The WHO report—which doesn’t count risks that depend on individual behavior, such as smoking and diet—looks at the environment broadly, including “physical, chemical, and biological factors external to a person” that can be modified. It focuses on environmental risks that are the product of the societal decisions that shape the world we live in. “Some of these environmental factors are well known, such as unsafe drinking-water and sanitation, and air pollution and indoor stoves; others less so, such as climate change or the built environment,” the WHO report says.

There’s a big dose of guesswork in trying to estimate the global toll of unhealthy surroundings. The actual share of deaths attributable to the environment is most likely somewhere in the range of 13 to 34 percent, according to the report. To get to those numbers, the WHO examined studies on risks for more than 100 types of diseases and injuries: how air pollution affects cardiovascular disease, for example, or how workplace stress affects mental health. The group also surveyed more than a hundred experts.

The types of diseases involved have shifted in the decade since the WHO published a similar report. More people around the globe have gotten access to clean water, sanitation, and less harmful household cooking fuels. That transition has led to a decline in infectious diseases. At the same time, non-communicable diseases like heart disease and cancer account for a growing share of death and illness worldwide.

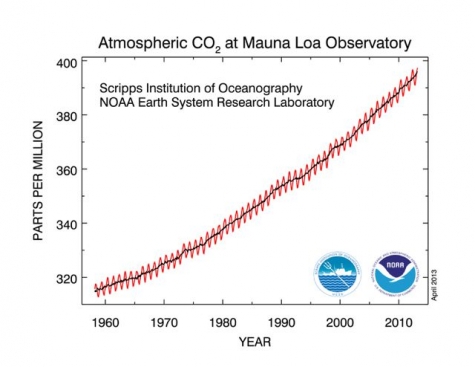

The WHO report may underestimate the full cost of environmental hazards on health, according to experts like Perera and Joseph Allen, an assistant professor at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. That’s partly because the effects of climate change are so difficult to predict, as the report acknowledges. “Climate change is exacerbating nearly every environmental health issue we have,” said Allen.

The good news is that the risks identified in the report are, by definition, modifiable. Straightforward measures such as greater access to clean water and hygiene could make an immediate impact. But because so much pollution and other environmental damage are consequences of commerce, fixing the problem would require changes to the way we do business. “Actions by sectors such as energy, transport, agriculture, and industry are vital, in cooperation with the health sector, to address the root environmental causes of ill health,” the report says.

The world has done it before, on both a small and a large scale. When Beijing put factories on pause to clear the air during the 2008 Olympics, babies born shortly afterward had a higher birth weight, researchers found. And in the United States, removing lead from gasoline—an effort opposed for years by the oil industry—was followed by dramatic drops in lead levels in children’s blood.