Union County, Florida is 250 square miles, nestled in the middle of the state’s pan—not the handle—about an hour southwest of Jacksonville and nearly as far from the state’s southern border. Residents depend on four things for their county’s survival: farming, trucking, timber, and the state’s department of corrections. It is the country’s third congressional district, the state’s smallest county, and the place in Florida that will take the hardest economic hit from climate change, according to a new study released today in the journal Nature.

The study takes six factors—temperature, rainfall, the effect of carbon dioxide on agriculture, mortality, crime, and labor and energy demand—and models them out to see how climate change will affect the American economy on the county level. They estimate that each 1.8 degree Fahrenheit increase in temperature will reduce the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) by 1.2 percent. But that cost won’t be borne equally. Areas in New England and the Pacific Northwest might actually experience a slight economic gain, while places in the American South are likely to experience significant economic damage. Climate impacts could diminish Union County’s income, for example, by 27 percent—as heat-related deaths and crime take a bite out of any increased agriculture.

“The current suite of computer models that are used actually treat the entire United States as a single unit, as though all the impacts that are going to be received are going to be received, on average, the same to everyone,” study author James Rising, an environmental modeler in the Energy and Resources Group at UC Berkeley, told PopSci.

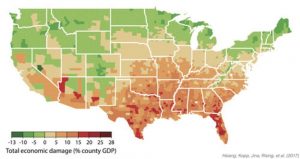

County-level annual damages in median scenario for climate during 2080-2099 under business-as-usual emissions trajectory (RCP8.5). Negative damages indicate economic benefits.

Global Policy Lab

But the new study provides a more granular look at the impacts—zooming all the way in to see the county level effects—so that local governments can better plan and adjust as the climate changes.

The business world, especially the insurance industry, is growing increasingly worried about how global warming will change their ability to predict risks; not just in regard to flooding, as is frequently considered, but also for things like crop insurance. If an insurance company can’t predict risks, they can’t provide insurance, and the economic system we’ve created begins to fall apart.

“There are a couple of aspects of this study that I think are important advances,” says Benjamin Preston, Director of the Infrastructure Resilience and Environmental Policy Program at the Rand Institute, who was not involved with the new study. “It’s not often that we see these kind of estimates in climate impacts on that sort of resolution, at the county level. I thought that was a particularly important contribution this paper is making in moving the science forward.”

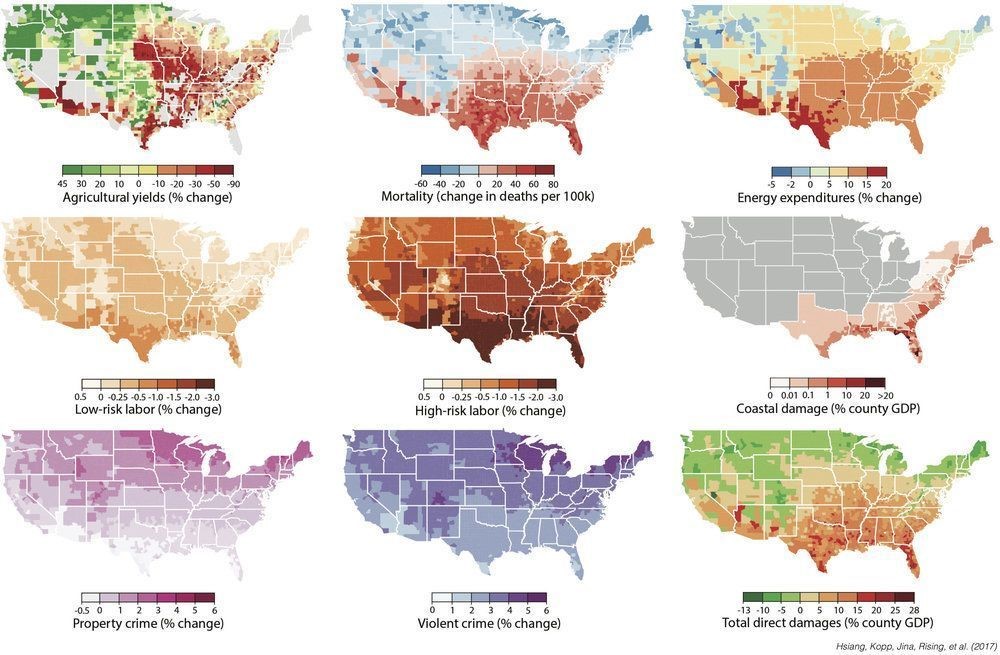

County-level annual damages in median scenario for climate during 2080-2099 under a business-as-usual emissions trajectory (RCP8.5). Negative damages indicate benefits. From left to right, top to bottom: percent change in yields, averaged for maize, wheat, soybeans, and cotton; changes in all-cause mortality rates, across all age groups; change in electricity demand; change in labor supply of full-time equivalent workers for low risk jobs where workers are minimally exposed to outdoor temperature; same as previous except for high risk jobs where workers are heavily exposed to outdoor temperatures; change in damages from coastal storms and sea level rise; changes in violent crime rates; changes in property crime rates; median total direct economic damage across all sectors.

Global Policy Lab

One of the study’s limitations is the fact that it only factors in some of the many potential impacts of climate change, but Rising acknowledges that shortcoming.

“We set a pretty high standard for what kinds of results and science we would incorporate into the analysis,” says Rising. “We only included response functions, which describe how people or sectors respond to weather, that had been previously published and that had a response that we could say was causal rather than correlation.”

In other words, some impacts haven’t been closely studied enough to assign a hard dollar amount.

“What’s the value of biodiversity, the loss of biodiversity,” says Preston. “That’s something that’s very difficult to quantify in economic terms, so it isn’t included in the study. But it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t keep those kinds of impacts in mind when we’re thinking about the overall net consequences of climate change.”

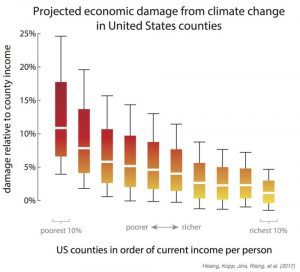

Range of economic damages per year for groupings of U.S. counties, based on their income (29,000 simulations for each of 3,143 counties). The poorest 10% of counties are the leftmost box plot. The richest 10% are the rightmost box plot. Damages are fraction of county income. White lines are median estimates, boxes show the inner 66% of possible outcomes, outer whiskers are inner 90% of possible outcomes.

Global Policy Lab

One finding from the study presents an incredibly macabre form of actuarial teeter-totter: as the temperature warms, more people die. Northern states appear to fare better than southern, but that’s just because the increase in deaths during the summer months there will be offset by a decrease in deaths during the winter months. And then, of course there’s the crime.

“Whatever your baseline temperature is,” says Rising, “for every additional Fahrenheit of temperature, people are more likely to commit violent crime, commit property crime, have arguments, yell at each other, and even have interstate and inter-group conflicts on country-wide scales.”

All of these factors conspire to put the South disproportionately in harms way.

“The South is already hot. And it turns out that when you’re hot and get hotter, things are going to be a lot worse for you than if you just have moderate temperature and you get somewhat warmer,” says Rising. “And it’s not possible to talk about that without pointing out that the South is a lot poorer, so an extra dollar that’s lost from the South because any of these factors isn’t the same as a dollar that might be gained in the North of the United States. It hurts people more. What we were able to see is that climate change is going to widen income inequality; it’s going to make it more difficult for areas in the South to provide for their citizens’ education and jobs and wellbeing across the board. “

If you live in a place that’s relatively well-off, according to the analysis, you’ll probably still be fine (financially, anyway). But poor communities will suffer.

All of this, however, comes with two caveats. The first, of course, is that the modeling is done with the assumption that we won’t make efforts to mitigate climate change.

“I often get asked at parties if it’s too late, as though if we don’t do a certain amount by a certain time the world’s going to explode,” says Rising. “I think it’s important to understand that there’s a lot of opportunity to use numbers from our paper to decide on what kind of responses we want to make.”

If we can keep warming under 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit), then the rising temperature is actually going to have a very small effect on GDP. But if we hit 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) of warming, things start to look dire. Experts recently put out an article claiming that we have just three years to start curbing carbon emissions before it was too late to prevent a 2 degrees Celsius increase.

The second, of course, is that the paper doesn’t take into account people’s attempts to adapt—because, well, we don’t really know how they’ll go about doing that. Climate change could drive people to move out of hard-hit regions, or convince the snowbirds who tend to migrate South for retirement to stay put.

And that same, unpredictable reaction will play out in other places—in Sub-Saharan Africa, for example—that are just as warm and getting warmer, with even less income and institutional support.

Source: Popular Science, Kendra Pierre-Louis, Jun 30th 2017 7:35AM